When I was growing up canned foods were a staple in our kitchen pantry and our meals. From canned green beans and corn as a dinner side dish to salads with canned peach or pear halves topped with a scoop of cottage cheese or canned asparagus and tomato aspic on a lettuce leaf topped with a dollop of Miracle Whip, canned foods were an essential part of my life. And the can-filled meals continued with my mom’s Friday dinner rotation featuring tuna noodle casserole created with canned tuna, cream of mushroom soup and peas and her spaghetti and lasagna with canned tomatoes as a key ingredient. Back then, canned foods were normal, not berated or relegated to second-class status as they are frequently characterized today. It’s sad because canned foods boast an array of benefits that often go unrecognized. So what better time to extol the virtues of canned foods than February, National Canned Food Month. Canned foods can… Boost nutrition: Packed within five hours of harvest, canned fruits and vegetables are at their peak of ripeness, flavor and nutrient content. Without any oxygen in the can, their abundant supply of vitamins and minerals are locked in at their original amounts until they are opened and eaten. Studies actually show that canned foods provide as much – and sometimes even more - nutritional value as fresh ones do. This makes sense when you consider that it often takes over three weeks for fresh produce to get from the farm to the supermarket while canned and frozen ones are packed within hours of picking. Research further documents that people who eat more canned food consume more nutrient-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, dairy and other protein foods compared to infrequent canned food users. They also have a higher intake of 17 essential nutrients including the shortfall nutrients identified in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans — potassium, calcium and fiber. Save money: Canned foods are a bargain both nutritionally and for your wallet! According to a 2014 study published in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, USDA Economic Research Service data revealed that canned vegetables may provide a cost savings of up to 20% over fresh and have a longer shelf life. Make meals in minutes: Already cooked, canned foods help you create meals in a flash. Canned fruits, veggies, beans and meat can serve as an ingredient in salads, sandwiches, soups, stews and casseroles. Canned vegetables are a great side, canned beans a savory main dish and canned fruit an easy dessert alone or added to yogurt or ice cream. The Cans Get You Cooking website boasts an assortment of recipes and videos to get you started. In addition, the Canned Food Alliance has recipes and an Essential Kitchen Toolkit to help you organize and stock your kitchen and plan and prepare meals. Reduce food waste: Half of all fresh produce in the U.S. is thrown away. Produce is lost in fields, warehouses, packaging, supermarkets, restaurants and at home. In fact, most Americans throw away about 15 - 20% of the fresh fruits and vegetables they purchase every year. Foods in landfills produce methane, a greenhouse gas associated with climate change. On the other hand, the peels, cores and other inedible parts of fruits and vegetables removed during the canning process are re-used as feed for farm animals or composted. Very little is wasted. Canned foods are non-perishable and have a long shelf-life, at least two years from the date of purchase when stored in moderate temperatures of 75° F. or less. That further decreases food waste. And the cans themselves can be recycled, also lessening environmental impact. Canned foods are not…. Highly processed: Canned foods are actually very minimally processed. After food is packed into sealed, airtight cans, heat is applied to kill microorganisms. Then the cans are heated under steam pressure at 240-250° F. for the minimum time it takes to ensure they are sterile but still retain optimum flavor and nutrition. No preservatives are added or necessary. So canned foods frequently sport some of the “cleanest” labels around. A quick look in my pantry reveals salsa style canned tomatoes with tomatoes, tomato puree, jalapeno peppers, Anaheim peppers, salt, dehydrated onion, citric acid, spices, acetic acid (vinegar), dehydrated garlic, calcium chloride; and canned pears with pears, water, pear juice from concentrate and canned Alaskan salmon with pink salmon and salt. High in salt and sugar: Only 11% of sodium in the diet comes from vegetables, including canned forms. And just 2% of added sugar in the diet comes from fruits and vegetables, including canned ones. For those who need to reduce salt, low sodium and salt-free canned foods are readily available. Research has demonstrated that simply draining and rinsing regular canned vegetables can reduce sodium by 41% while draining alone lowers it by 36%. Less canned fruit is now packed in heavy syrup as compared to light syrup, 100% juice and no-added sugar varieties. Lower quality than fresh: Some have the mistaken belief that canned foods are the “seconds” or lower grade than those that are sent to the fresh market. I was on a canned fruit and vegetable harvest tour in September 2017 and learned this is not true at all. The peach orchard and tomato farm we visited were grown exclusively for the cannery down the road. We literally followed the freshly-harvested produce down the road to the canning facility and watched as it was unloaded and transported through the canning process. As I mentioned earlier, these canned fruits and veggies go from field to can in less than five hours. Unsafe due to protective linings: Can linings actually ensure the safety, quality and nutritional value of the food inside. Years of testing is conducted prior to approval of any coatings used in can linings. One coating, bisphenol A (BPA) has come under fire in recent years as a result of preliminary studies written about in the popular media. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration along with safety agencies around the globe continue to affirm its safety based on a vast body of research. FDA states on its website, “People are exposed to low levels of BPA because, like many packaging components, very small amounts of BPA may migrate from the food packaging into foods or beverages. Studies pursued by FDA's National Center for Toxicological Research have found no effects of BPA from low-dose exposure.” But due to consumer concerns about BPA many companies are using or transitioning to new can coatings without BPA. Putting it all together Canned foods can go back in your shopping cart and pantry and on your menu and plate. They’re nutritious, delicious, safe, convenient, non-perishable and economical. So next time you’re in the supermarket, take a stroll down the canned food aisles and stock up on some of the 1500 varieties of always-in-season, canned foods available year-round.

3 Comments

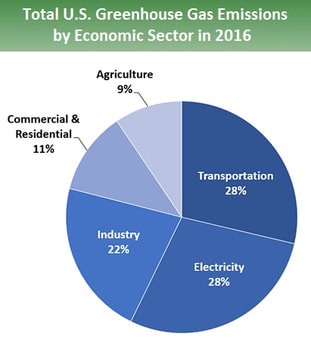

I’m not a beer drinker. But if I was, the Super Bowl commercial that would have tempted me to try their brand was definitely Stella Artois. At an upscale restaurant, waiters collide and drop trays as Carrie Bradshaw and The Dude forgo their traditional Cosmopolitan and White Russian for a Stella or “Stella Ar-toes” as The Dude called it. During the scene where a glass of Stella is drawn from the tap and the head leveled off with a knife, I could almost taste and smell the beer. Fast forward to another beer commercial, this time from Bud Light. Instead of touting their product for its taste, quality and fun they chose to resort to the newest marketing tool of the food and beverage industry, fear. In a medieval scene, Bud Light brewers mistakenly receive a barrel of corn syrup for their beer. So they harness up their horses to pull the corn syrup barrel first to Miller Lite brewers, who say they’ve already received their corn syrup delivery, and then to the Coors Light brewery that is happy to claim it. The last line of the ad assures us that Bud Lite is “brewed with no corn syrup.” Does this really make any difference? Let’s review “Beermaking 101.” The beer brewing process starts with grains, usually barley but also rye, corn, oats or wheat. What these all have in common is they are primarily composed of starch, a complex carbohydrate. Starch is made up of hundreds of glucose (a simple sugar) molecules bound together. After being heated and dried, the grains are immersed in hot water where the enzymes in the grains release the glucose from the starch and create a sugar syrup, which is the basic ingredient for making beer. Whether its barley syrup, rye syrup, corn syrup, oat syrup or wheat syrup, chemically it’s all the same – glucose (sugar) mixed with water. The body cannot tell the difference between glucose from any food or beverage source. It is identical. The only difference is each grain imparts a different flavor to the beer. So why does the Bud Light commercial portray beer made with corn syrup in a negative light? It is most likely to play on consumers’ misplaced fears about high fructose corn syrup and/or GMO corn. As I mentioned earlier, corn syrup used in making beer is 100% glucose. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is a product created from corn syrup by converting some of the glucose into fructose so that it has about 50% each, the same as white sugar and honey. Created in the 1970’s, it replaced sugar as an ingredient in many foods and beverages because its sweetness was nearly identical to sugar but it was easier to use, more stable and functioned better in products. But furor ensued in the 2000’s when some scientists suggested that the increase in HFCS intake might be the reason obesity in the U.S. was on the rise. There is no scientific evidence to support this and numerous studies have found no difference in the body’s use of sugar vs. HFCS nor any increased risk of negative health effects. And according to two different government surveys the intake of all sugars, including HFCS, has gone down since 1999 while obesity has continued to rise. In addition, GMO corn is safe. There is no difference in nutrition, health or safety between GMO and non-GMO corn. GMOs are not “in your food.” Agricultural biotechnology, commonly called GMO, is a method of growing crops like organic or conventional farming. A single genetic trait from another plant is inserted in the DNA of the crop seed so it can resist a certain insect or weed killer, tolerate drought so it can grow with less water or increase the amount of a vitamin or other nutrient in a food. And if there is any slight genetic difference in the corn itself, it would not show up in corn syrup. That’s because DNA is always combined with protein and there is no protein in corn syrup. It is 100% carbohydrate in the form of sugar. So what’s the bottom line when it comes to choosing beer? Make your decision as you would with any food or beverage on taste, cost, quality and enjoyment. Or support your local brewery like Coors if you live in Colorado or Shiner if you’re in Texas. Don’t base it on negative marketing and misleading claims of fear. A Look at the EAT-Lancet Report: Can a Near-Vegan Diet Save the Planet and Feed the World?1/24/2019  A new report surfaced last week in a noted British medical journal, The Lancet, that recommends a near-vegan eating style as a way to promote greater sustainability of the food system, lessen the environmental impact of animal agriculture and improve health of the world’s population. Of course, this is the same journal that published a notorious study – later debunked and retracted – suggesting a link between the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine and autism, which ignited the current anti-vaccination movement. Created by the EAT-Lancet Commission, a collaboration between the EAT Forum (founded through the Stordalen Foundation), the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Wellcome Trust, the investigation and report were funded by EAT and the Wellcome Trust. The founder and chair of the Stordalen Foundation is a billionaire Norwegian physician who is a vegan. The co-chair of the EAT-Lancet Commission and lead author of the report is a Harvard professor well-known for his strong stance against meat in the diet. But he’s not a fan of potatoes, either. Wait, aren’t they plants? Reading beyond the headlines hailing this report, is it really advisable for everyone to adopt a near-vegan eating pattern? Before we call on governments and health agencies around the world to endorse such a radical change in traditional food production and consumption, we need to explore the societal, environmental and nutritional implications of doing so. Is a near-vegan diet more sustainable? As technology has transformed our world over the past century, people have become more concerned about its impact on the environment. Like most other industries, agriculture has embraced technology to help farmers produce food more efficiently. And this is a good thing when you consider that 40% of the labor force in the U.S. was engaged in farming 100 years ago while only 2% is today. That means farmers must produce more food for a population that has tripled from 104.5 million in 1919 to 326.8 million today while the amount of farm land and water has remained the same or been reduced. And they have been very successful in doing that. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. agriculture accounts for around 9% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions compared to 28% for electricity, 28% for transportation and 22% for industry. And a 2017 study revealed that removing all animals from the food supply and replacing all of those calories with plant crops would only reduce total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 2.6%. Farmers from all sectors of the industry are working toward sustainability in their practices to protect and enhance the land and conserve water and other resources so their farms can continue to produce food for future generations. And equally important, creating a sustainable farm allows them to make a living so they can stay in business so we’ll all have food to eat. U.S. cattle ranchers are producing the same amount of beef today as they were 40 years ago with one-third fewer cattle. Likewise, through improved cow breeding and feeding, dairy farmers produce milk today with 90% less land and 65% less water than in the mid-20th century, resulting in a 63% smaller carbon footprint. In 1950, there were 25 million dairy cows but only 9 million today while milk production has increased by 60%. And in the egg industry, innovations in nutrition and breeding since 1960 have increased egg production by 27% while decreasing daily hen feed by 26%, water use per dozen eggs produced by 32% and hen death by 57% while lowering greenhouse gas emissions by 63%. Finally, half of all fertilizers used in the U.S. to grow fruit, vegetables and grains are organic fertilizers made from livestock manure. Eliminating animal agriculture would mean replacing them with chemical fertilizers that are very energy intensive to produce. Will a near-vegan diet feed the world? In the U.S. only 1 in 10 adults currently eats the minimum number of fruits or vegetables recommended in federal dietary guidelines according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study. Dietitians are continually challenged to help people find ways to enjoy eating more of these nutrient-rich foods. Will eliminating most of the meat, eggs and dairy foods from the food supply force folks to eat more of these wholesome plant foods? The even bigger question: is there enough land to grow the amount of produce and grains we would need to replace the calories and other nutrients provided by animal foods? Will eliminating livestock grazing free up more land to produce more food for people to eat? According to the World Bank, 37.2% of the world's total land area is considered agricultural but only 10.9% is arable or capable for growing crops like fruits, vegetables and grains. That’s less than a third of the total agricultural land. The other 70% of agricultural land is marginal and not suitable for growing crops due to lack of water and/or poor soil quality. It is only good for grazing ruminant animals that can digest grass - goats, sheep and cows. In addition, 85% of cattle feed is not digestible by humans like grass, wheat and oat straw, sugar cane tops and corn silage (husks, leaves and stems). Thus, these ruminant animals convert food with poor-quality protein from plants inedible for humans into high-quality protein food with a variety of nutrients not always plentiful in plant-based foods. Will a near-vegan diet adequately nourish the world? I love fruits, veggies and grains. I eat a lot of them. But I also enjoy eating meat, dairy and eggs. I have friends who are vegans and vegetarians and I respect their right to choose that eating pattern and they respect mine to include animal foods in my diet. A vegan diet can be nutritionally adequate and promote health just like those including animal foods. Having said that, it is more challenging to meet these nutrient needs but it can be done with careful planning and some supplementation of vitamins only found in animal foods. The bigger question is whether we can nourish an entire population (country, continent or world) with only plant foods. The previously mentioned 2017 study compared the current U.S. food production system to a modeled one where animal agriculture and animal-derived foods are eliminated. The plant-only agriculture system produced 23% more food but met fewer of the essential nutrient requirements for people in the U.S. The plant-only diets projected more nutrient deficiencies, a need to consume a greater amount of food and more calories. Researchers concluded that removing animal foods from the U.S. food supply resulted in diets that did not support people’s nutritional needs without nutrient supplementation. Animal foods like meat, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy provide high-quality protein with all the essential amino acids in amounts necessary for building and maintaining all body tissues. In addition, each of these foods supplies additional nutrients that are not always present in significant amounts in plant-based foods.

On the other hand, fruits and vegetables contribute nutrients like vitamins A and C, folic acid, potassium, fiber and phytonutrients that are not provided by or are present in smaller amounts in animal foods. And grains are a source of fiber, several B vitamins along with iron, magnesium, and selenium. That’s why a diet with a variety of foods from all groups helps ensure an adequate intake of all nutrients. Leaving out one or more groups makes it more difficult. For example, you would have to eat 1.25 cups cooked spinach (50 calories) or 3.75 oranges (335 calories) to get the same amount of calcium in a cup of 1% low-fat milk (100 calories). And it takes 3 cups of cooked quinoa (660 calories) or 1.7 cups of black beans (385 calories) to obtain the protein in 3 ounces of lean cooked beef (156 calories). In addition, some vegetables, grains, nuts and seeds contain oxalate and phytates that can bind minerals like calcium, iron and zinc and keep them from being absorbed. On the other hand, the lactose and vitamin D in milk enhance the absorption of calcium. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s MyPlate, the graphic representation of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, is a plant-based eating pattern with three-quarters of the plate comprising fruits, vegetables and grains. Including animal foods in the diet can help boost intake of plant foods. One way to encourage people to eat more plant foods is to pair fruits, vegetables and grains with meat, eggs and dairy: yogurt and fruit, cheese and bread, beef/pork/chicken in a vegetable stir-fry with rice, a fish taco in a whole grain tortilla with chopped tomato and bell pepper or an omelet layered with vegetables and cheese. Putting it all together Sustainability is essential to protecting the environment and feeding and nourishing the world. In the U.S. farmers and ranchers have worked diligently to become more efficient in producing more food with fewer resources. This has significantly reduced the impact on land, water and chemical use. Unfortunately some other countries, especially developing ones, have not been as successful or even have the ability to harness technology to improve productivity. Rather than radical changes to the world’s food system, a better solution would be to direct resources to helping farmers throughout the world to work more efficiently and sustainably. Because sustainability is also about sustaining health through sufficient food that delivers adequate nutrition as well as sustaining farmers’ abilities to maintain financial security in order to continue producing enough food, it cannot simply be viewed through the narrow lens of environmental impact. Food and meals are an integral part of our lives. People choose foods for many reasons, not just for nutrition and health but also for taste, cost, availability and cultural, religious and family traditions. Dietitians play a critical role in helping people adopt eating habits that not only ensure health but also accommodate these other factors. Finding appealing ways for individuals to consume more plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts and legumes can boost nutrition and still be compatible with eating appropriate amounts of animal foods to obtain essential nutrients. Creating this balance will have long-term influences on enjoyment of eating, nutritional adequacy, health status and the environment of our planet.  The latest food-shaming headlines attack a vegetable! Yes, it’s the poor potato, the latest poster child for a “bad” food. No less than a Harvard professor declared potatoes “starch bombs” in a recent New York Times article that also claimed potatoes’ “high glycemic index” is linked to heart disease, diabetes and obesity. While the study cited in the story is actually about the relationship between fried potatoes and health, the story itself seems to be more of an all-out assault on potatoes in general. As my stock-in-trade is “Eating Beyond the Headlines,” let’s take a closer look at the claims in this article and the real facts and science related to potatoes and their place on your plate. Claim #1: Potatoes rank near the bottom of healthful vegetables. This first claim continues with, “and lack the compounds and nutrients found in green leafy vegetables.” While it’s true that potatoes and other white vegetables don’t contain the beta-carotene plentiful in deep orange and dark green ones, that doesn’t mean potatoes don't deliver valuable nutrients. A small baked potato with the skin contains a mere 130 calories and 3.6 grams protein along with 22% of the daily recommendation for potassium, 19% for vitamin C, 13% for fiber, 10% for magnesium and 9% each for folic acid and niacin. To further validate potatoes’ nutritional contributions, a 2012 Purdue University roundtable session, “White Vegetables: A Forgotten Source of Nutrients” brought together researchers and scientific experts who provided substantial evidence that eating white vegetables, such as potatoes, can increase shortfall nutrients, especially fiber, potassium and magnesium, as well as help increase overall vegetable consumption in the U.S. Claim #2: Potatoes are “starch bombs.” Starch, the main source of carbohydrate in our diets, is composed of hundreds of glucose molecules. Therefore, it’s known as “complex” carbohydrate as compared to sugars, which are “simple” carbohydrate. Glucose, a simple carbohydrate or sugar, is the body’s primary fuel source. Without it our bodies couldn't function! There’s really nothing bad about starch. If fact, some of the starch in potatoes is not even digested - resistant starch. “Resistant starch acts as a prebiotic or food for the gut bacteria (probiotic)," explains registered dietitian nutritionist, Angela Lemond, owner of Lemond Nutrition in Plano, Texas. "Potatoes become even more of a resistant starch when they are cooked and then cooled down. Either let them cool before eating or refrigerate them and cut them cool into a salad.” At a time when many folks are concerned about gut health and getting more prebiotics and probiotics to enhance their intestinal microbiome, potatoes offer a natural way to do that without expensive supplements. Claim #3: Potatoes have a high glycemic index, linked to higher risk of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. According to Melissa Joy Dobbins, a registered dietitian nutritionist and certified diabetes educator in the Chicago area, it's not the glycemic index of individual foods that matters, but the glycemic load of the entire meal. "Most people don’t eat a potato by itself but instead as part of a mixed meal with other foods, likely including some protein and fat. Therefore, the glycemic load of the meal counteracts the glycemic index of individual foods," she says. More evidence to dispute this claim is documented in a 2016 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Researchers reviewed 13 studies investigating the role of potatoes in obesity, diabetes and heart disease and concluded that they did not provide strong evidence of an association between intake of potatoes and risks of these conditions. Claim #4: “Two-thirds of the 115.6 pounds of white potatoes Americans eat in a year are in the form of French fries, potato chips and other frozen or processed potato products according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.” When you break it down it’s not as bad as it might sound. Dividing 115.6 pounds by 365 days a year equals just 5 ounces of potato per day or the size of the small potato mentioned above. Furthermore, 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data confirmed that white potatoes provide only 4% and French-fries just 2% of an American’s total calories intake. The survey also revealed that Americans average a mere 1.5% of their daily calories from French fries or 31 calories for a typical 2,080 calories/day. And just one in 8 males and one in 10 females consumes French fries on any given day. Even for those with the highest French fry intake (90th percentile of consumption or higher), men ate 134 calories and women 118 calories/day, the equivalent of half a small serving of fast-food fries. The Bottom Line A single ingredient, food or meal is not responsible for weight gain, nutrition status or health. The total diet over time is what matters. Singling out one food and blaming it for chronic disease or obesity is not only wrong but is counterproductive to encouraging healthful eating habits. Potatoes have long been a popular staple food in the American diet and deliver taste, nutrition and health benefits at an affordable price.  As most of you know, misleading headlines about food and nutrition are a huge concern of mine, thus the brand of my business and blog, “Eating Beyond the Headlines.” A recent set of headlines drew my ire even though they weren’t related to my usual stock-in-trade of refuting fear and misinformation about foods, ingredients and modern agriculture. Instead it was an article about a study that evaluated the effect of diet and lifestyle changes in people at risk for type 2 diabetes. I first came across the headline in my Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics SmartBrief email that arrives daily in my email box filled with headlines and brief summaries of food and nutrition stories in the popular press. Imagine my surprise when I read “Diabetes risk reduction not tied to lifestyle advice, study shows.” Hmmm. I learned and have always promoted diet, exercise and lifestyle as key components in preventing and managing type 2 diabetes. Clicking the link to navigate to the news story, I find a different headline, “Lifestyle advice alone fails to reduce type 2 diabetes risk.” The key word here is "alone." That's not reflected in the SmartBrief email headline. Reading the article, it states, "Participants attended four 2.5-hour group education sessions at 2, 6, 12 and 24 months after baseline. Sessions covered general information about diabetes and diabetes risk/prevention, nutrition and dietary recommendations, advice on moderate physical activity, and information on physical activity opportunities." And just 50% attended at least 3 of the sessions. So we might conclude that it wasn't the lifestyle interventions that failed, but the subjects’ failure to use them. Next I downloaded the original journal article, “Basic lifestyle advice to individuals at high risk of type 2 diabetes: a 2-year population-based diabetes prevention study,” published in BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care. Note that this title is not at all negative about the role of diet and lifestyle in type 2 diabetes as the previous ones. In the conclusions the authors state, "In summary, the substantial 2-year diabetes incidence, the consistent increases in glycemia and BMI, the relatively low participation, and the low proportion achieving substantial weight reduction indicate that our low-grade intervention with basic lifestyle advice did not have clinically meaningful effect on diabetes prevention overall or in subgroups by age, sex, education level, depressive symptoms, BMI, physical activity, or family history of diabetes." Key terms to note are "low participation," "low proportion achieving weight loss" and “low-grade intervention with basic lifestyle advice.” I haven’t worked in clinical dietetics or medical nutrition therapy for years but even I know that a “low-grade intervention with basic lifestyle advice” is not the ideal way to treat patients with or at risk for type 2 diabetes. So I went to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics position paper, “The Role of Medical Nutrition Therapy and Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) in the Prevention and Treatment of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes.” This paper documents the effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy (MNT) provided by RDNs for the management of diabetes, advising that individuals with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes should be referred to an RDN for individualized MNT upon diagnosis and at regular intervals throughout life as part of their treatment regimen. Specific evidence cited includes:

According to registered dietitian nutritionist, Melissa Joy Dobbins, also a certified diabetes educator and spokesperson for the American Association of Diabetes Educators, “Nutrition counseling for diabetes is more than just giving someone information or 'lifestyle advice.' It takes time. While group classes can provide an overview, meeting with a registered dietitian nutritionist is more likely to be effective because of the individualized plan that is created together between the patient and dietitian. And research shows that more than 10 hours of diabetes self-management education and support is necessary to achieve benefits that have major impact.” The bottom line: when you read a headline in the popular press that tells you nutrition therapy is not effective or a food or ingredient is bad for you, don’t accept it as fact without further investigation. Contact a registered dietitian nutritionist or check the website of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics for more information. And please, please do not tweet or post the story to social media without getting the facts. Sources cited:

In May, I began consulting with the California Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement to help spread the word about the safety and nutritional value of leafy greens. I was not compensated for writing this blog and the information is based on facts from a variety of sources. As a registered dietitian nutritionist working as a communications consultant to the food, nutrition and agriculture industries, I address misinformation and sensational headlines about food and nutrition on a daily basis. I try to reassure people that it’s safe to eat foods and ingredients like red meat, eggs, wheat, potatoes and sugar for which there is no scientific evidence of harm when eaten in moderation as part of a balanced meal pattern. But sometimes scary headlines can take a real food concern and create more fear than is warranted. So how do we know when the fear is real and when it’s not? The recent romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak is a perfect example. TRACKING THE SOURCE On April 13, officials confirmed that the lettuce contaminated with E. coli came from the Yuma, Arizona area. Agencies like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration sprang into action to make sure the affected lettuce was removed from the food supply. Supermarkets and restaurants were alerted to stop selling and serving lettuce from Yuma and consumers were advised to throw out any romaine in their refrigerators if they could not identify where it was grown. Obviously, caution about eating romaine was essential. If you read past the scary headlines, government officials were clearly limiting the alert to romaine produced only in the Yuma region. Meanwhile, leafy green industry groups were updating consumers that romaine currently being sold in stores and restaurants was from California, not Arizona. Both were advising consumers not to eat romaine unless they could confirm it wasn’t grown in Yuma. FEAR FLOURISHES On April 29, I ate lunch with my mother in the dining room of her independent living retirement community here in Dallas. As we filled our plates at the salad table, one resident remarked, “I will be so glad when we have romaine again. I am so tired of pale lettuce.” More than two weeks after stores and restaurants were advised to pull romaine from the Yuma area, fear continued to reign about any romaine lettuce. Granted, as we age our body's immune system is less effective and the elderly are more susceptible to foodborne illness. So I can give my mom’s place a pass for their extreme caution, even though there was virtually no chance any tainted romaine was still in the food supply. On May 16, the CDC said the last shipments of romaine lettuce from the Yuma growing region were harvested on April 16, the harvest season was over and it was unlikely any romaine lettuce from the Yuma growing region was still available in stores or restaurants due to its 21-day shelf life. Yet when I had lunch with my mom again on May 27, romaine lettuce was still not being served. And as of June 22, she reported, “we probably won't ever have it again.” ENSURING SAFETY We are fortunate in the U.S. to have the safest food supply in the world. However, an occasional outbreak of foodborne illness does occur but this is by far the exception and not the rule. Along with USDA and FDA regulations for farming and food processing, additional safety nets are in place to further assure safety and decrease health risk, like the Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement (LGMA). This past March I attended the Produce for Better Health Foundation conference in Scottsdale, Arizona where I met an LGMA representative and learned about their safety program to help ensure leafy greens produced in our country are safe to eat. The majority of leafy greens in the U.S. are grown and harvested under the LGMA initiative to minimize food safety risks on the farm. Every day, over 130 million servings of leafy greens are safely produced under this mandatory government food safety program. It verifies farming practices using government audits and requires that members be in 100% compliance at all times. They must create a written food safety plan, test irrigation water and monitor worker practices, like proper handwashing. In fact, many major restaurant and supermarket chains require the LGMA certification for leafy greens they purchase. MOVING FORWARD After this outbreak, the produce industry created a special task force to examine how romaine came to be the source of illnesses. No one wants these kinds of tragic outbreaks to occur – least of all leafy greens farmers. The leafy greens community is committed to producing a safe product and we need to trust they will continue to improve on their already excellent safety record. As a registered dietitian nutritionist, leafy greens are my go-to vegetable. I enjoy them every day and recommend them to others. They are nutrient-rich, boasting vitamins A and K, folate, potassium, iron, calcium and fiber while low in fat and calories. So be assured that romaine is a nutritious choice and safe to go back on your plate. For more information and tips and videos on how to keep your greens safe in your home: http://safeleafygreens.com Photo credit: pixabay.com |

Neva CochranMS, RDN, LD, FAND Archives

November 2022

BlogsStay Safe at the Plate this Thanksgiving

The Real Truth about MSG: Myths, Science, Guidance An Aspiring Registered Dietitian: Advocating for Farmers, Consumers and Nutrition Strategies that Benefit Both Banned from Amazon: My DASH Diet for Dummies Review! Healthy Eating Resolutions You're Sure to Keep Same Song, Second Verse: The Dirty Dozen is Still a Dirty Lie Juice Can Go Back on Your Table Frozen Berries: Nutritious, Delicious and Safe to Eat The Lowdown on Lettuce and Listeria The Dirty Dozen is a Dirty Lie It’s in the CAN: Convenient, Affordable and Nutritious Meals When it comes to beer, choose taste not fear A Look at the EAT-Lancet Report: Can a Near-Vegan Diet Save the Planet and Feed the World? Peeling Back the Facts on Potatoes: Don’t Sack ‘Em Diet, Lifestyle and Diabetes: The SmartBrief headline that was really dumb Romaine Can Go Back on Your Plate |